CPU Scheduling in Virtual Environment¶

One of the capabilities in virtual environment is the ability to run multiple virtual machines in a physical hypervisor host. Servers consolidation allows us to reduce datacenter footprint and maximise ROI on physical hardware. However, this introduced an added level of care to balance performance management and consolidation ratio.

Running multiple VMs on a physical hypervisor means that these VMs will be sharing the resources on a single physical server. On a macro level, this includes CPU, memory and disk. In a micro level, the VMs will also be sharing the interrupts, processor caches, SMP interconnect (e.g. Intel’s QPI links) bandwidth, PCI-e bus resources etc. Resource sharing must be coordinated appropriately to ensure certain level of fairness can be achieved. Many settings/tunings have been developed (and are still under ongoing improvements) to enhance scheduling algorithms in order to solve the complexity of resource scheduling.

This article will concentrate on the high level CPU scheduling impact on the virtualised workloads. For more in-depth details on how CPU scheduling work inside hypervisor, please refer to VMware CPU scheduler whitepaper [1] , and Microsoft Hypervisor Top-Level Functional Specification [2] .

CPU Over-commit: Impact¶

In a virtualised environment, CPU over-commit (provisioning more virtual cores than the available physical cores) are most often used to consolidate servers. Historically, CPU utilisation in the physical environment were generally under-utilised (average 15% utilisation). And based on this figure, the belief was that we were then able to consolidate multiple servers to make up for the un-utilised CPU resources. Hence, CPU over-commit was used to aggregate and consolidate workloads.

In a perfect world, that would have been a great approach (and continues to be a good enough approach for many general use cases). However, in the real world, mixed workloads behave differently and CPU tend to fluctuate spontaneously due to randomness in workloads under various demands. Coupling the randomness of CPU spikes and scheduling latency due to insufficient physical cores, workloads running on a host with over-commit CPU will not have deterministic and consistent CPU performance response.

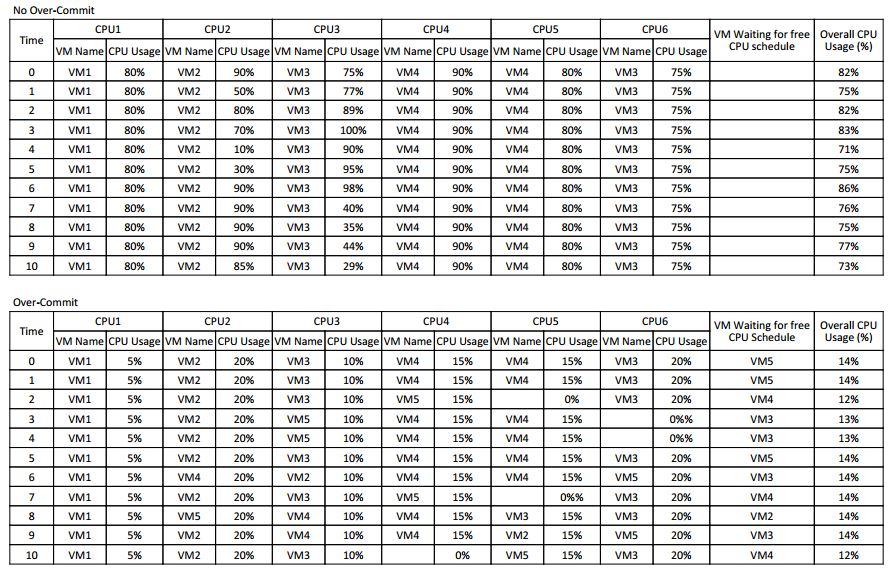

See the following (overly simplified) diagram depicting the time-sharing nature of CPU scheduling.

The top table shows an example of a host with no CPU over-commit, i.e., vCPU to pCPU is at 1:1 ratio. In this case, there are always a free physical core for the hypervisor to schedule virtual CPU to run. The CPU response and performance in this case would be relatively linear and consistent independent of utilisation.

The bottom table shows an example of a host with CPU over-commit, i.e., more vCPU allocated than the available pCPU. In this case, the hypervisor will need to time-share the physical CPU, and regularly place VMs in wait queue. This irregularity of response in terms of CPU latency means that it is difficult to expect a consistent performance from application’s point of view.

CPU Ready¶

CPU Ready metric is very well documented by VMware (and also in Microsoft Hypervisor TLFS [2]). It is one of the main metrics that VMware use to determine possible CPU contention. In a nutshell, CPU Ready means the amount of time the VM’s vCPU is spending in standby queue (ready-to-execute) while the hypervisor is looking for available physical CPU time to schedule to run it.

Note

In Microsoft Hypervisor TLFS document, under section 10.1.3 Virtual Processor States, specifies a high-level states of virtual processor. Ready is defined as ready to run, but not actively running because other virtual processors are running. This pretty much sums up what CPU Ready is, applicable to both VMware and Microsoft hypervisor.

There are various guidelines as to what percentage of CPU Ready stat is considered acceptable (i.e., 5%). However, these are general views from the academics. In practice, there are no rule-of-thumbs, as it pretty much depends on the business requirements, applications, users expectations and many other factors. Some workloads are fine with 10% CPU Ready, but some would struggle when CPU Ready hit close to 3% (or even much lower if the workloads demand near real-time response).

To make the matter more complicated, the measurement and calculation of CPU Ready in VMware is very much depending on the sampling period and number of vCPUs as well. The CPU Ready metrics in VMware is a summation counter over the sampling period. For example, if the sampling period is 20 seconds (the real-time performance view taken from vSphere Client), and a 1 vCPU VM has recorded 100 milliseconds of CPU Ready, this means that over the interval of 20 seconds (or 20,000 milliseconds) that 1 vCPU spent 100 milliseconds in ready queue, which is effectively 0.5%

However, for VMs with multiple vCPU, the overall CPU Ready metric is the aggregate total for each of the vCPU’s CPU Ready value. For example, if a VM with 2 vCPUs has an overall CPU Ready value of 1500 milliseconds, convert this straight to percentage becomes 7.5%, which is higher than the “recommended” 5%. But this value is the aggregate of 2 vCPUs, so we would need to divide that by 2 to get the per vCPU ready value. Note that this is not very scientific, as there is no way to measure how much overlap each vCPU CPU Ready over the interval, we can only take a general approach based on statistical approximation.

CPU Ready Red Herring¶

It is not entirely correct to assume that high CPU Ready value as the proof that a host is overloaded. There are cases where VMs could exhibit very high CPU Ready value even if it is not utilising high CPU and the underlying host has low CPU over-commit ratio.

If a VM is constantly toggling between sleep and wake call, the hypervisor will constantly go through the cycles of scheduling the VM from wait->ready->run. This will invariably increase the CPU Ready value, even on a host that is not busy.

The CPU Ready value can also be influenced by how the guest OS behaves. For example, let us consider some Linux VMs that are based on some older mainline Linux kernel releases (e.g., RHEL 4-5, SLES 9-10), which uses tick-based mechanism to handle timer. These VMs could have the timer interrupt set to 1000Hz, which means that these VMs, together with local APIC timer on each CPU to drive the scheduler, will generate 2000 timer interrupts for VMs with 1 vCPU, or 3000 interrupts per second on VMs with 2 vCPUs.

The larger the amount of vCPUs are assigned to these VMs, the more interrupts per seconds they will generate, which can severely degrade system performance. The effect of this is that the VMs will be frequently and constantly demanding the hypervisor to schedule CPU time and then go into idle state again shortly after that. For idle VMs, although the CPU utilisation in MHz are low, their CPU Ready value will be high due to them generating lots of interrupts (thousands of wake-sleep cycles).

There are ways to work-around this that could assist with performance gain. However, these workarounds may or may not be easily available to change, depending on which Linux kernel or distribution. Refer to VMware KB on timer interrupts, Oracle blog’s - Speeding up your Linux Guests and Fedora mailing list

Note

Newer Linux kernels moved away from tick counting to “tickless” implementation, which is much more efficient.

CPU Reservation Does Not Really Solve CPU Ready¶

CPU Reservation in vSphere provides the capability of customising the priority on how the underlying CPU resource gets shared out to VMs. If VM Greedy-VM has a CPU reservation set higher than other VMs, the ESXi host will favour the Greedy-VM over others when slicing the CPU time sharing resource. This will certainly reduce the CPU ready of Greedy-VM (although it will not be able to rid of CPU Ready, but merely reducing it), however, the downside of that is we have now effectively taken the time sharing credits from other VMs and transfer it to Greedy-VM therefore making other VMs CPU Ready worse.

In a service provider environment, where each customer should be treated equally (in practice this is generally not true), by exercising reservation we are inducing ‘unfairness’ into the time-sharing scheduling. Effectively, this is similar to robbing a customer’s credit and give it to another customer.

Relationship between CPU Usage vs CPU Ready¶

A common misconception is that if a host’s CPU usage is high, therefore CPU Ready value of the VMs running on the host must be high. This is not true. CPU usage and CPU Ready are two different independent measurements. CPU usage in vSphere metrics is a measurement of CPU clock utilisation in percentage or MHz, whereas CPU Ready is usually used to measure CPU scheduling latency.

As shown in the CPU Scheduling Event Tables, we can see that even though the VMs in the No Over-Commit host are constantly at 70% to 80% CPU utilisation, there is no VM waiting for free CPU schedule, therefore these VMs would have minimal latency introduced by the CPU scheduler.

Whereas in the Over-Commit example, the VMs are using less than 15% CPU on average, but due to CPU over-commit, there are VMs waiting for free CPU schedule at all times. In this case, the VMs are seeing high CPU latency despite not using much CPU.

On a host with overcommit CPU, high CPU utilisation quite often causes high CPU Ready due to probability that we would hit CPU contention in busy systems. Therefore, in practice, when looking an overcommitted environment, administrators often make a direct correlation between CPU utilisation and CPU Ready - rightly or wrongly.

Footnotes

| [1] | VMware CPU scheduler whitepaper |

| [2] | (1, 2) Microsoft Hypervisor Top-Level Functional Specification |